The 1453 Fall of Constantinople: Causes, Siege, and Consequences

Explore the 1453 Fall of Constantinople: understand the clash between the Ottoman and Byzantine Empires, Sultan Mehmed II's ambitions, the 55-day siege, and its lasting impact on world history.

4/24/20257 min read

The Fall of Constantinople: A Turning Point in History

The Fall of Constantinople in 1453 stands as one of history’s most transformative events, signaling the end of the Byzantine Empire and the rise of the Ottoman Empire as a dominant power. On May 29, 1453, after a grueling 55-day siege, Ottoman forces under Sultan Mehmed II breached the ancient walls of Constantinople, capturing the city that had served as the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire for over a millennium. This conquest not only altered the political landscape of Europe and the Middle East but also had profound cultural, religious, and intellectual repercussions, influencing the course of history for centuries.

This comprehensive exploration delves into the reasons behind the war, Sultan Mehmed II’s motivations for targeting Constantinople, the historical context, the siege itself, and the far-reaching consequences of this pivotal moment. By understanding these elements, we gain insight into why this event remains a cornerstone of world history.

Historical Background: The Decline of Byzantium and the Rise of the Ottomans

To grasp the significance of the Fall of Constantinople, we must first examine the historical context that set the stage for this monumental clash.

The Byzantine Empire’s Decline

The Byzantine Empire, or Eastern Roman Empire, was the continuation of the Roman Empire in the East after the Western Roman Empire’s collapse in 476 AD. Founded by Emperor Constantine the Great in 330 AD, Constantinople was strategically positioned at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, controlling vital trade routes via the Bosphorus strait. Renowned as “New Rome,” the city was a bastion of Christian orthodoxy and Greek culture, fortified by the formidable Theodosian Walls.

By the 15th century, however, the Byzantine Empire was a shadow of its former glory. Centuries of external conflicts, including the Crusades, internal political strife, and the devastating Black Death (1346–1349), which killed nearly half of Constantinople’s population, had eroded its strength. By 1450, the empire was reduced to the city of Constantinople and a few surrounding territories, with a population of just 40,000–50,000, down from 400,000 in the 12th century (Britannica). The Byzantine military, reliant on mercenaries and limited allies, was ill-equipped to face a formidable foe.

The Ottoman Empire’s Ascendancy

In contrast, the Ottoman Empire was a rising power. Originating in Anatolia in the late 13th century, the Ottomans expanded rapidly, conquering much of the Balkans and Anatolia by the mid-15th century. By 1453, they controlled territories on both sides of the Bosphorus, effectively surrounding Constantinople. The Ottoman sultans viewed the city as the ultimate prize, a conquest that would solidify their dominance and legitimize their claim as successors to the Roman Empire (World History Encyclopedia).

This stark contrast—a declining Byzantine Empire versus an ascendant Ottoman Empire—created the conditions for the inevitable conflict.

Why Did the War Begin? Reasons for the Ottoman Attack

The Ottoman decision to besiege Constantinople was driven by a combination of strategic, economic, and symbolic imperatives.

Strategic Importance of Constantinople

Constantinople’s location made it a linchpin for trade and military control. Positioned on the Bosphorus strait, it regulated commerce between the Black Sea and the Mediterranean, generating significant revenue through tolls. Controlling the city also meant dominating access to the Balkans and Central Europe, facilitating further Ottoman expansion. Mehmed II recognized this, building the Rumeli Hisarı fortress in 1452 to block aid from reaching Constantinople and secure the strait (Wikipedia).

Weakened Byzantine Empire

By 1453, the Byzantine Empire was critically vulnerable. Its territorial holdings had shrunk to a few square kilometers, and its economy was crippled by trade disruptions and the Black Death’s demographic toll. The city’s defenses, though historically robust, were understaffed, with only about 7,000 defenders, including mercenaries, compared to the Ottoman army’s 60,000–80,000 troops (Lumen Learning). This disparity made Constantinople an enticing target.

Historical Precedent

Constantinople had faced numerous sieges over the centuries, surviving most but falling to the Latin Crusaders in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade. The city was recaptured by the Byzantines in 1261, but this history demonstrated its vulnerability. The Ottomans, aware of these precedents, believed that with superior resources and technology, they could succeed where others had failed.

Ottoman Expansionism

The attack on Constantinople was the culmination of ongoing Byzantine–Ottoman wars. The Ottomans had steadily eroded Byzantine territories, capturing key regions like Thrace and Anatolia. Constantinople, as the last major Byzantine stronghold, represented the final step in consolidating Ottoman control over the region and eliminating a persistent rival.

Reason for Attack Details Strategic Importance Controlled Bosphorus trade routes and access to Europe. Weakened Byzantine Empire Reduced territory, population, and military capacity. Historical Precedent Previous capture in 1204 showed the city was not invincible. Ottoman Expansionism Part of ongoing wars to subdue Byzantine territories and assert dominance.

Why Did Sultan Mehmed II Want Constantinople? The Sultan’s Motivations

Sultan Mehmed II, who became sultan in 1451 at age 19, was a visionary leader whose motivations for capturing Constantinople were both personal and strategic.

Personal Ambition and Legacy

Mehmed II sought to establish himself as a formidable ruler, challenging the Christian powers of the Balkans and Aegean. His youth led some European courts to underestimate him, but he was determined to prove his prowess. Capturing Constantinople would earn him the title “the Conqueror,” ensuring his place in history. In a speech to his advisors, he emphasized the struggles of his forefathers and the need to secure a prosperous kingdom for future generations (Wikipedia).

Military Strategy and Innovation

Mehmed II was a pioneer in military technology, commissioning massive cannons like the Basilica, a 27-foot-long artillery piece capable of firing 600-pound balls over a mile. These weapons were critical in breaching the Theodosian Walls, which had withstood sieges for centuries. His strategic foresight was evident in the construction of Rumeli Hisarı and the innovative tactic of transporting ships overland to bypass Constantinople’s harbor defenses (EBSCO Research).

Religious and Political Claim

Mehmed II saw himself as the successor to the Roman Empire, adopting the title Kayser-i Rum (Caesar of the Romans). This ambition was intertwined with religious zeal, as Islamic prophecies foretold the conquest of Constantinople by a Muslim ruler. By capturing the city and converting Hagia Sophia into a mosque, Mehmed II fulfilled these prophecies, strengthening his legitimacy in the Islamic world and shocking Christian Europe (TheCollector).

Unwavering Determination

Despite offers from Emperor Constantine XI to pay higher tributes, Mehmed II was resolute in his goal of conquest. In his final war council, he overcame opposition from advisors like Halil Pasha, who favored negotiation. His determination reflected both personal conviction and a strategic vision to unite the Ottoman Empire under a single, iconic capital.

Mehmed II’s Motivation Details Personal Ambition Sought to prove himself and earn the title “the Conqueror.” Military Innovation Used advanced cannons and tactics to overcome Constantinople’s defenses. Religious/Political Claim Aimed to fulfill Islamic prophecy and claim Roman imperial legacy. Determination Rejected Byzantine tributes, insisting on total conquest.

The Siege of Constantinople: A 55-Day Struggle

The siege of Constantinople, from April 6 to May 29, 1453, was a meticulously planned and fiercely contested campaign.

Preparation and Initial Moves

Mehmed II prepared extensively, building Rumeli Hisarı in 1452 to control the Bosphorus and assembling an army of 60,000–80,000, including elite Janissaries and artillery units. The Byzantine defense, led by Emperor Constantine XI, numbered only about 7,000, bolstered by Genoese and Venetian volunteers. Constantine XI fortified the city, stockpiling supplies and rallying defenders (Shadows of Constantinople).

The Siege Begins

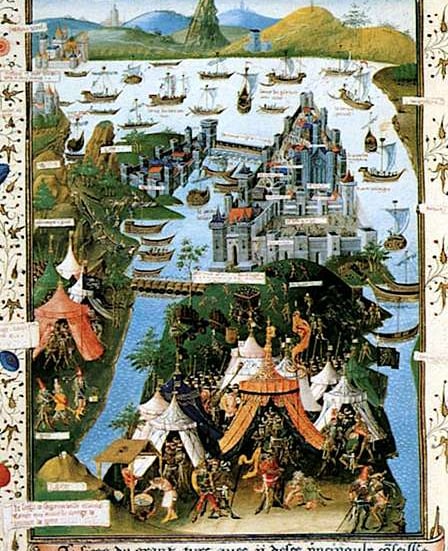

On April 6, 1453, Ottoman forces encircled Constantinople. Mehmed II’s artillery, including the Basilica, began a relentless bombardment of the Theodosian Walls, creating breaches despite Byzantine efforts to repair them. The defenders, though outnumbered, held their ground, relying on the city’s fortifications and their resolve.

Naval Operations

The Ottomans sought to blockade the Golden Horn, Constantinople’s harbor, but a Byzantine chain blocked their ships. In a daring move, Mehmed II ordered his fleet to be transported overland from the Bosphorus to the Golden Horn, bypassing the chain and threatening the city from the water (Britannica Siege).

Final Assault

After weeks of attrition, Mehmed II launched a decisive assault on May 29, 1453. Ottoman troops attacked multiple points, exploiting breaches in the walls. Despite fierce resistance, the defenders were overwhelmed. Emperor Constantine XI reportedly died in combat, casting off his imperial regalia to fight alongside his men. By day’s end, Constantinople had fallen (Medieval Manuscripts).

Aftermath and Impact: A New Era Begins

The fall of Constantinople had immediate and enduring consequences, reshaping the world in profound ways.

Transformation of Constantinople

Mehmed II declared Constantinople the new Ottoman capital, renaming it Istanbul. He converted Hagia Sophia into a mosque, symbolizing the shift from Christian to Islamic dominance. The city became a thriving center of Ottoman culture and governance, solidifying the empire’s regional power (Britannica Siege).

End of the Byzantine Empire

The conquest marked the definitive end of the Byzantine Empire, concluding the Roman Empire’s 1,500-year legacy. The loss of Constantinople was a psychological blow to Christian Europe, which had viewed the city as a bulwark against Islamic expansion (Lumen Learning).

Catalyst for the Renaissance

The fall prompted an exodus of Greek scholars to Western Europe, particularly Italy, bringing classical texts and knowledge. This influx fueled the Renaissance, revitalizing art, literature, and science through the rediscovery of Greek learning (The Collector).

Long-term Geopolitical Shifts

The Ottoman victory enabled further expansion into Europe, leading to centuries of conflict with Christian states. The fall is often cited as a marker of the transition from the Middle Ages to the early modern period, reflecting shifts in warfare, trade, and cultural exchange (World History Encyclopedia).

Conclusion: A Legacy That Endures

The Fall of Constantinople in 1453 was a defining moment that closed one chapter of history and opened another. It marked the end of the Byzantine Empire and the ascendancy of the Ottoman Empire, driven by the strategic imperatives of the time and the relentless ambition of Sultan Mehmed II. The conquest reshaped political boundaries, spurred cultural and intellectual movements like the Renaissance, and set the stage for centuries of interaction between Europe and the Islamic world.

Today, the legacy of this event endures in Istanbul’s vibrant history, the enduring influence of Ottoman culture, and the intellectual heritage of the Renaissance. The Fall of Constantinople remains a testament to the power of vision, strategy, and the tides of history that shape our world.